I’ve been working on a short comic for a very long time now, about how someone’s dog spontaneously transforms into a human one day and runs away, only to later track down their owner to go on a date that turns into a one night stand. Oops, spoilers lol. Determining the outcome of this story has been really difficult though, and I want to speculate on why and what that has to do with speciesism, which is a fancy way of referring to the different ways we discriminate against animals. In this essay, I want to try and shed light on how the different kinds of relationships we form with non-humans acts as a reflection for those we build with each other, with ourselves, and with our environment. In formulating my argument, I’m primarily drawing on the work of Timothy Morton, who’s work has greatly informed my own critical inquiry.

I’m pretty sure the difficulty I’ve been experiencing in moving forward with this comic derives from my own hesitation when negotiating the arbitrary roles that I ascribe to animals, as far as how they serve humans. For instance, the character that was once a dog and who turns into a human is modeled after characteristics in people that I judge to be dog-like. Therefore, he’s ingratiating, eager, moralistic, and lacks self-awareness. He’s also more than that though, because I wanted to illustrate how he’s learned to adapt to humanity. Therefore, he’s also insecure, hypocritical, and aloof. This cross-section of human and animal affect both codifies these characteristics, but also dissolves them, because it reveals how mutable the boundaries of what we call “human” really are. Just as any person is irreducible to some mythic conception of nature or essence, I believe the same can be said for animals, which suggests that being anything isn’t monolithic. Even having an evolutionary predisposition is only one facet of any living thing’s overall makeup; or as Donna Haraway states, “historical specificity and contingent mutability rule all the way down, into nature and culture, into naturecultures. There is no foundation; there are only elephants supporting elephants all the way down.”1 This shouldn’t imply that everything about living things is entirely up for grabs, because, once again, we’re subjects of a certain amount of evolutionary and biological determinism, but that is only one piece of the pie. Bearing this in mind, I think the struggle I’ve been encountering with my comic is that I wasn’t treating my dog-person as the individual that they are, and was instead trying to meet some prepackaged interpretation of what a dog-person should be. The furries would be sorely disappointed.

Let’s make this topic more relatable though: owning a pet is weird. Can we as pet owners at least accept that as a reality and move on? I got a cat a few months back and we are deep in figuring each other out. Her name is Oryx and she’s extremely shy and will only let myself and my boyfriend pet her. Oryx has a sweet and slightly bitchy temperament, and spends the majority of her days perched at the window in our living room, staring out at the overgrown backyards of neighboring apartment buildings, waiting for a bird to fly by so that she can follow it with her incredibly sharp senses. In fact, I’m convinced that it’s her senses that keep her so on-edge, which is probably why she hides even when she hears someone exiting the elevator outside our apartment. Perhaps it’s for this reason that I’ve gotten into the habit of asking my partner the rhetorical question: Do you think we should let her go?

While it is fun to consider setting my cat free so that she can skitter across the streets of Brooklyn and potentially get hit by a car, I think the resounding opposition to this idea is reflective of a certain bias that pet-owners are bringing to the table, and I wonder whether it’s one that solely has the animal’s best interests in mind. If we begin to turn our gaze less to the intention of a cat, for instance, and more to its human companion, the question becomes whether we are willing to recognize how much stock we place in our own involvement in the lives of our pets. For instance, it would appear that cats are generally unphased by who their owners are, as long as they’re fed and cared for—so why give ourselves so much credit for their wellbeing? Your cat may enjoy getting belly rubs and fancy wet-food that’s mailed to your door, but it literally doesn’t give a shit about you. I suppose what I’m getting at is that one’s relationship with an animal is only one piece of that animal’s overall experience. Oryx may benefit from me being her guardian, but she’ll never have all her needs met, and it’s for that reason that she may never reach her full potential whereby she can exercise whatever bliss is her birthright. She was lifted from the street as a kitten, after all.

The conceit that one can own another living thing is probably what lies at the heart of what makes any interspecies relationship seem so uncanny. I mean, no one is out here claiming to have a relationship with an animal unless there is some element of ownership that is creating the conditions for that relationship. Do we agree? Of course, no relationship is one-sided, which is why the whole concept relies on the notion that two or more parties are negotiating their respective agencies, and are even potentially relinquishing those agencies, for the sake of abiding by mutual expectations. Given this reasoning, it would seem worth acknowledging that pets aren’t just owned but also have their own stake in being domesticated and cared for, which is why it’s easy to argue that it’s cruel to let cats live in the street, because the streets are indeed cruel! That said, I believe that this mentality of “protection” and “stewardship” also validates a legacy of animal abuse and general negligence on the part of humans to account for the intrinsic differences that form the basis for interspecies relationships in the first place. I’m interested in unpacking to what end we’re willing to make concessions for what we call a relationship, so that we may consider at what cost we let a cat’s claws sink into our flesh in order to justify holding them in between a rock and a hard place. Ultimately, my intention is not so much to trace the legacy of wrongs that has resulted in the mass-incarceration and mass-extinction of animals we are witnessing today, because that approach does little to speculate on paths forward. The lack of futurality that our current, cynical moment is beckoning us to relent to doesn’t leave much room for self-awareness, in my opinion, because it’s basically a mode of relating to the world from a post-apocalyptic perspective, which is another way of saying: you’re off the hook! Instead, I want to tease apart different models of speciesism to arrive at an alternative, and hopefully more inclusive, vision of solidarity.

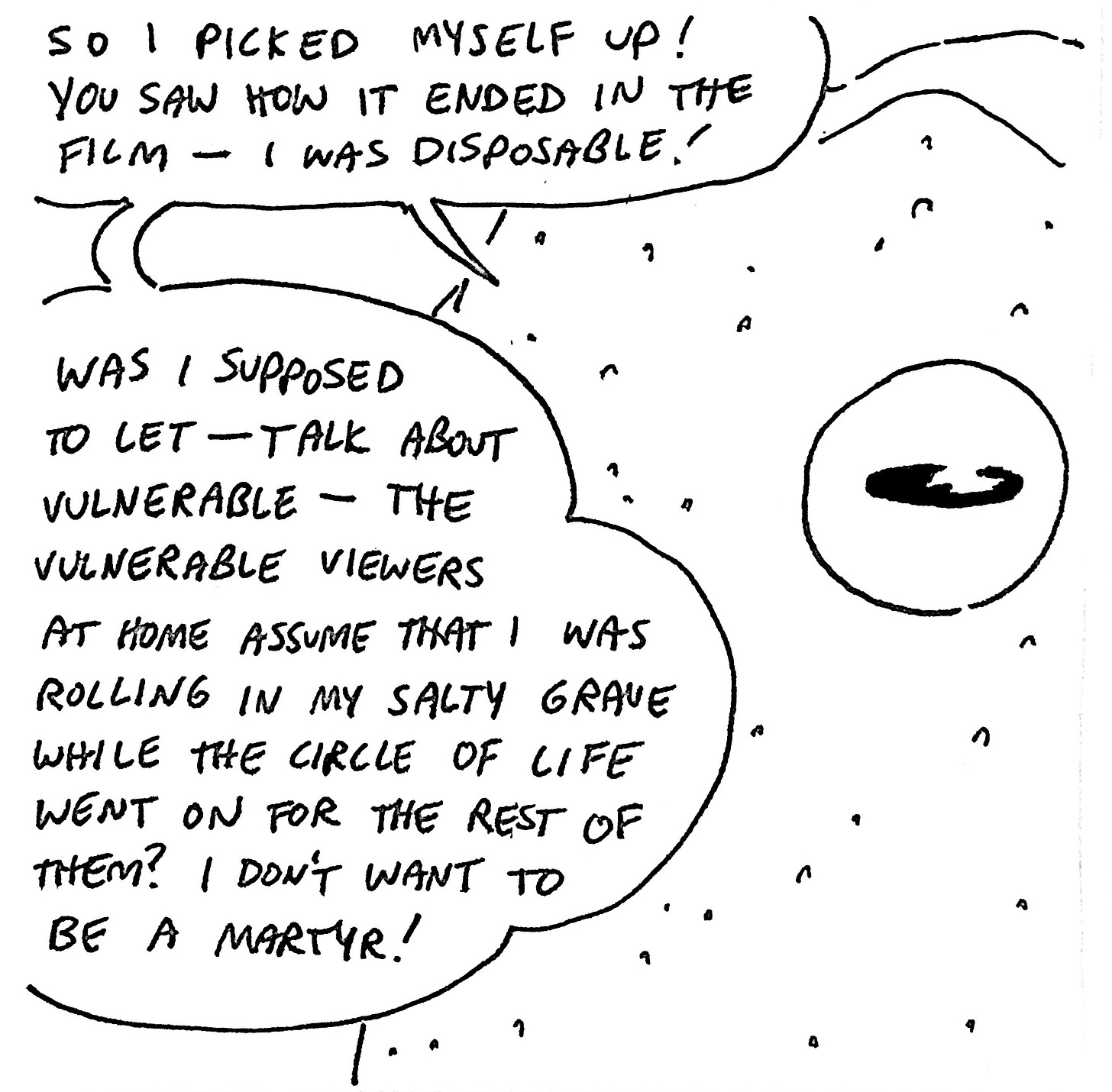

How we see animals matters. In the past I’ve shared some of my skepticism of animal advocacy as seen through nature-documentary. The basis for my critique was that these programs elicit a mode of bridging the divide between people and animals via human stewardship of our dying, fragile planet. In the process, our perception of documented animals and their environments becomes an extension of the kinds of idealizations of nature that have enabled its abuse. I tried to elaborate on this by drawing a comic in response to My Octopus Teacher, that I posted on Instagram a few years back, in which the octopus from the film appears on a daytime talk-show to give her side of the story.

To be fair, My Octopus Teacher is a great film for what it is, and I’m not out here trying to contest its accolades, because I’ve done that already elsewhere, and because there’s a lot worse you could do as far as what constitutes as responsible media. However, in the spirit of speculation, I don’t think MOT actually has the octopus’ best intentions in mind, because none of us have any idea of what an octopus’ intentions actually are, let alone whether they can or should even be qualified as having intention in the first place.

Nature documentaries represent a tradition of capturing flora and fauna as if they were pieces of a larger network, like trading cards in a game that in this case we’ve dubbed nature. That’s what makes the combined genres of “nature” and “documentary” especially enticing, because they evoke a sense of wonder in what’s out there, as if gotta catch ‘em all is meant to galvanize us into protecting all the Pokémon instead of doing what we’re actually here for, which is to collect them and make them battle. Another version of this can be seen in the Instagram account for National Geographic photographer @joelsartore, who is the founder of Photo Ark. The account has 1.6 million followers and features an effort to document every animal on Earth in order to raise awareness around biodiversity. Each post on the account is of a different animal placed in a vacuum-like setting, in which the subject has been removed from its context, and the result is truly as biblical as it implies. A flamingo appears to exist in empty space, solely in and of itself and with no reference to its environment, its kin, or whatever conditions have resulted in it being placed there. What’s at stake is certainly the posterity of the flamingo, but to suggest that our awareness of a species requires that we view them as if they could be manufactured for the convenience of our consideration strikes me as antithetical to the cause. This may seem like a stretch, but it reminds me of that scene from the horror film, Cabin in the Woods, in which the characters realize that the monsters that have been attacking them for the duration of the movie are actually compartmentalized in a massive complex underground, whereby booby-traps release them to their whim. In the case of the Photo Ark, documenting animals isn’t for their preservation as much as to normalize their utility. A flamingo is never just a flamingo, just as a ghost is never just a ghost unless it is purely trying to spook us, which I’d have a hard time believing. Ghosts exist, but not like that.

To be fair, what I believe both MOT and Photo Ark get right is that they focus on individuals rather than entire species. However, the irony is that in representation of undomesticated animals, an individual is typically used to address an entire species, which suggests that any individual member of that larger whole is essentially replaceable, like a cog in a machine. This kind of ecological thinking is more anthropocentric than it is ecological, because it fails to account for how, as Morton suggests, “an entity contains a potentially infinite regress of other entities. The entity is literally out-scaled by its parts. It is bigger on the inside, like Pandora’s jar. Which means, logically, that it’s smaller on the outside, so that, however absurd and amazing it sounds, we need to say ‘the whole is always smaller than the sum of its parts.’”2 Given this reasoning, if we begin to operate within the conceit that the environment, for instance, is ontologically smaller than the conditions that fulfill it, the implication is that any one of those conditions is actually much more real and potentially tangible than the big E Environment, because each of those conditions is also producing further conditions that comprise their own environment. For instance, a flamingo isn’t just a flamingo, but it eats minerals in mud that makes its feathers pink, and pink is a color that we love to see but for some reason apply a gender to, so that all the different ways that we could interpret pink get absorbed by Pink, Inc. It would be so easy for us to just let pink be a color that is contingent on an infinity of criteria, but instead we uphold a religious adherence to what pink must mean so that we can protect it as a symbol of what all the other pinks are ultimately serving.

Furthermore, if we continue to hold that the whole is actually less than the sum of its parts, then wouldn’t that imply that an individual octopus is actually more substantial than the fight to save octopi everywhere? An individual octopus, for instance, and as the film illustrates, has entirely its own thing going on apart from anything David Attenborough or whomever has to say about it, just as nothing about you or I is reflective of all of humanity. This being the case, it strikes me as problematic that the perspective of MOT presupposes that this particular octopus deserves to be captured and archived, for the betterment of all octopi. Are we willing to consider that no one deserves representation in order to survive, though? Isn’t that like suggesting that it’s up to us as to whether something deserves to live? What if we were willing to just let the octopus live without needing to grant it the right? What if we just left it alone?

It reminds me of this moment in which my partner and I got strapped taking care of a whole litter of baby bunnies because their mother was brutally slaughtered by my mom’s cat while we were spending an extended visit there. I don’t blame my mom for dropping them in my lap, because that is a mother’s instinct or whatever. My younger brother’s reaction, however, was to just let them be, because otherwise we were only going to extend the process of their inevitable demise. We decided to give them a fighting chance though, which was a choice we felt validated in when that evening it not only torrentially downpoured, but a lightning bolt touched down in seemingly the exact spot where their warren used to be! The outcome was such that we fed them goat’s milk twice a day for two weeks while they rapidly developed in a box filled with grass and hay. We began with seven, and had two left by the time we released them into the woods behind my mom’s house, because the rest did die for reasons we couldn’t determine despite all of our care and research. In hindsight, I realize how my brother’s desire to leave them be is reflective of the same kind of call for abstinence that I’m arguing for in the context of nature documentaries. However, again, if the parts are indeed greater than the whole, then in this case, I think our own perspectives should be taken into account, in which our desire to aid in their survival wasn’t so much an intention on our part to abide by some Darwinian fatalism, but instead to compensate for the conditions that had resulted in their precarity in the first place, which in this case was the presence of an invasive species that hunts for sport. Then, there’s also the bunnies themselves to take into account, who became terrified of us as soon as they developed fully functioning vision—they were always going to take what they could get and then hightail it. This is meant as an example of warring ecologies that we can actually find stock in because they are more real than whether all bunnies deserve better or deserve to die. Rather, these ones were simply dropped in my lap!

Let’s head back to civilization: rats abound in Brooklyn. On my block alone, they are tearing up the landscaping around a building because the soil is riddled with holes that lead down into what one can only imagine is a complex system of tunnels accommodating their seething, scurrying masses. On one occasion, I was walking home at night and a rat the size of my foot literally slammed its entire weight into me, and I didn’t regret it! However, the city has instituted new, state of the art rat-killing chambers that essentially lure them into a box where they die of asphyxiation or something thereof.3 The result is akin to the kind of mass-executions reminiscent of state-mandated genocide. This is nothing new. Humans and rats have always been in conflict—from plague to famine. Obviously, this transspecies symbiosis is one that benefits rats more so than it does humans, but I refer to it as symbiotic because infestation and death would appear to be the currency we are willing to exchange in order to maintain such a toxic relationship. We could release the cats into the streets and let them have at it with the rat hordes, but instead they remain indoors, pining after something to kill. Again, it is not my intention to argue on behalf of cat-liberation per se, as much as to address the conditions of pet ownership for the sake of speculation. Rats as a pestilence are the direct result of the dichotomy we continue to uphold of human versus nature, where in this case, nature is anything that acts as a reminder of human supremacy. Meanwhile, trash bags are piled up on the curb because we expect garbage-trucks to haul them away, whereby all that crap will end up in a land-fill where it will have run its course, but before that happens, rats will have burrowed into the warm recesses of human refuse; they’ll have used their expert noses to smell out the most attractive options; they’ll swim their languid bodies through shit like Templeton does in Charlotte’s Web; and they’ll drag entire slices of pizza back to their nest to feed their young. A city like Brooklyn is an untenable ecosystem, and represents the inevitable intersections that arise between the infinite number of smaller ecosystems it contains. Perhaps this is why we refer to the city as a concrete jungle, because we recognize that when systems are thriving, that’s probably because they are in conflict with each other. When we address the “rat problem” what we’re actually addressing are a multitude of other problems that are coming together at the point at which rats are most benefitting.

It begs the question, what kinds of systems, or ecologies, are intersecting to produce the pet industry for what it is today? Here’s one example: I live in a gentrified neighborhood. That is to say, I’m contributing to gentrification in a Black neighborhood. The thing that white gentrifiers like myself love to do is identify the problem in other white gentrifiers, whether because they don’t know how to talk to the locals but do know how to judge them, or because it costs literally nothing to absolve oneself of any association to the very systems that they oppose by projecting it onto others. In any case, it’s come to my attention that white people in my neighborhood all have dogs. My interpretation of why this is the case requires relaxing our grip on the expectation that animals should be subjected to ownership, so that we can better identify which conditions are intersecting to result in what I am suggesting is always a coincidental situation. My read on white people not leaving their apartment without a dog in tow is that, in my neighborhood especially, they are ashamed to face the music when they walk out into the world. Confronting the reality of white privilege, especially after spending hours absorbing it on social media via the rhetoric of black liberation in the privacy of one’s home, poses itself as a daily hardship. The answer is to never leave the comfort of one’s own property that acts as a filter between them and the world, as if they’d never left their apartment. Dogs are a perfect buffer because they need to be walked, and because they are cute, which draws attention away from whomever they are with. It’s not that different from benefiting from an emotional support animal, or even using a service dog, in that an animal is being used to fulfill a certain desire on the part of its owner. For this reason, dogs can be racist.

Again, this can’t be the only explanation for the abundance of dogs in my neighborhood, though, because every dog represents not any one kind of relationship, just as they represent more than just their significance within a relationship. Dogs can be individuals, too! Not only that, but as we’ve discussed, what you project onto someone or something may be reflective of the intersection of yourself with that thing, but it’s hardly indicative of the entire pie. For this reason, it also bears acknowledging that New Yorkers, among everyone else, have suffered a pandemic that has forced them indoors for the past two years, wherein animal companionship has presumably stepped in as an important aid in times of mental duress. A dog is bigger than a pandemic, because you can see it, pet it, even let it lick you if you’re lucky. Perhaps in the face of so many imperceptible threats, having a very real, a very actual presence of an animal can be grounding and even affirming. For dogs, this probably meant more time spent with their owner, like in the case of one Mr. McCormick, who, in regard to his own dog, states for the Times, “‘If I go to take out recycling or the garbage, or go get my mail, he will howl like a Costa Rican monkey, and it will sound like there’s a murder going on in my house,’ [in which he describes] behavior that arose only since the start of the pandemic. ‘He knows I’m just going to be gone for three minutes, but it doesn’t stop me from being able to hear him all the way down in the elevator.’ Mr. McCormick has mostly stopped going to restaurants, and has not gone on vacation since the start of the pandemic, largely to avoid separation from his dog.”4

I think it’s time to come full-circle. When I got a cat, I noticed that I began to talk with other cat-owners about living with a cat. It’s worth mentioning that I’d always grown up with cats, but in a more rural setting, so raising a cat in my apartment was an adjustment. It seems like cat-lovers across the board can all agree that cats never have all their needs met, which we can only do our best to compensate for. I’m especially fond of the healthy load of delusion cat people exercise in these conversations though, in which they remark on how “happy” their cat is with their new toy, or how their cat is “content” to just lay about the house unseen to everyone. Palliative qualifiers are used for pets to better assimilate them to our own needs and preferences. This confidence in how much one can claim to know about their animal companion is related to the kind of perspective that allows us to see them purely as creatures of instinct and evolution that must make due amidst the harsh reality of survival of the fittest, but survival has nothing to do with it, because we’re talking about pets, right? When we get to see others as merely subjects of their environment and predisposition, it allows us to more easily empathize with their struggle. Like when we watch a baby wildebeest get mauled by a pack of wild dogs, we feel pity for it but accept that “that’s life” and at least the dogs won’t go hungry. By giving ourselves access to their experience, we grant ourselves the privilege of exercising what feels like empathy, which is a feeling we’d all like to feel capable of exercising, right? What if empathy shouldn’t require that we witness someone else’s pain, though? What if we could instead trust in the reality that pain is assured in life, and treat each other accordingly? To demand evidence is akin to expecting remuneration from a victim for your capacity to relate to their experience, but this seems to be the norm. I’d like to think that a more constructive way to exercise empathy involves accepting that it applies to every individual and their subsequent, interwoven ecologies, instead of to some larger, ideological cause. This is why, for example, philanthropy doesn’t work, because it relies on the notion that people must be poor and needy in order to necessitate aid.

Another example of this hypocrisy can be seen in how white supremacy appropriates the rhetoric and aesthetics of bodies that are subject to discrimination and abuse. Again, the very exposure to and representation of people’s suffering acts as a catalyst for the engendering of a reactionary empathy that operates to view disempowered people as subjects of their environment who’ve just gotten caught up in the legacy of their persecution. I call it empathy because that is what we want to call it when what we are truly doing is pitying the plight of others. Constructs like social Darwinism illustrate how the distribution of power between adjacent groups doesn’t lead to the dissolution of that power but its further concentration, just as Capitalism appropriates forms of nonconformity that ultimately become commodified. If it’s given that the parts exceed the whole, we can put forward that solidarity itself would seem to be oxymoronic if it’s predicated on the expectation that everyone coexists in harmony, but this is the narrative that modernism sold to us vis a vis the advent of multiculturalism. I’m not trying to say that everyone should be fighting in the streets and that human difference is insurmountable, but that difference is intrinsic to solidarity—difference on an individual level, which is difference on an ecological level.

The idea that true solidarity is located in radical individualism sets itself up for the woke, knee-jerk reaction of those who’d like to argue that that is exactly what the neoliberal agenda wants for us. The difference though, is that Musk and Zuckerberg want to sequester us into machines that carry our personhood into the smooth-brain future, but this model of individualism is predicated on the assumption that death and its incumbent manifestation of the body are enemies of life, to the extent that who we are is somehow only part of the big picture, which, in this case, can be found in progress, efficiency, and, I’d like to argue, the soul. The notion that we can easily transcend our bodies to one day witness a future thousands of years from now, if not thousands of lightyears away, requires that our very humanity relies on such a mind-body binary. What if we don’t have a soul, though? What if, instead, we have bodies and organs that are made up of shifting conditions and ecologies that are so diffuse that they completely fail to satisfy whatever singular, overarching mission this alleged soul expects. Perhaps this is why we’re seeing the resurgence of anti-abortion rhetoric, because according to pro-life logic, a threat to one unborn fetus is a threat to all of humanity, as if life were in need of sustaining at all costs, regardless of its quality or care. Meanwhile, the bodies of childbearers become the replaceable cogs in the machine. No, that is not the individualism I am referring to here. Instead, I’d like to suggest that we accept and embrace the radical complexity of being ensconced in overlapping bodies, cultures, and histories.

I think this instinctual cynicism we’re feeling about “the greater good” is perhaps why we’re seeing so many manifestations of anthropomorphization in popular media today, and especially animation and comics. In the midst of the mass-extinction event that we are currently witnessing, it would seem fitting that consumers would seek to disassociate from the kinds of moralizing attached to apocalypse narratives and would therefore seek alternatives to a monolithic conception of humanity. Shows and movies like Bojack Horseman, the Sing franchise, or Beastars feature a running cast of characters that each in their own way exemplify the expectations of the species they resemble, and yet each has their own, individual issues to sort out as well. In this context, the Darwinian implications of power relations inherent in coexistence submits to a process of negotiation and compromise rather than all-out war, or as Thomas Lamarre states, in regards to the aesthetics of animalism as they appear in anime and manga, “two things happen when the translation of race war into species war entails a transformation of racial others into cute nonhumans. On the one hand, there is a sort of ideological operation or abstraction at work, a decoding and recoding of international relations into species relations. This procedure imparts a sense of overcoming racial, ethnic, and national divisions and conflicts. Entrenched divisions and segregations are at once evoked and radically shifted. Due in part to their address to children or family audiences, manga and manga films impart a sense of play, which promises a dramatic decoding of divisions and segregations. Rivalry among cute little animals not only makes military conflict look like play, it pitches it as cooperative and coproductive interaction. Simply put, this is not ‘survival of the fittest’ or ‘nature red in tooth and claw.’ The result of decoding and recoding is a multispecies ideal. The multispecies ideal (or more precisely, multi-species coding) jives with Japanese wartime thinking about coprosperity, pan-Asianism, and ‘overcoming modernity.’”5 Decoding and recoding, to me, sounds like the inevitable process of constantly remaining vigilant to the needs, desires, and differences of those in my immediate vicinity, in flux with shifting environments, algorithms, genders, statehoods, legacies, and inclinations. The far-right at least got one thing right: this is truly the future the left wants.

To end on a personal note: Oryx, my cat, isn’t blissful, nor is she miserable. She has her good days and her bad, like you or I. For a minute, I was convinced that there was nothing I’d be able to do to ingratiate myself to her, but with time, I’ve come to realize that that perspective was more so a reflection of my own desire to mean as much to my cat as she does to me. The reality is something different though, and it’s one that’s contingent on whether I’ve given her wet-food with fish or turkey that day, or if I’ve played with her for at least thirty minutes, or if she’s seen anything interesting out the window, or whatever genetic predisposition her ancestry awarded her with, or if music is being played from a car on the street, or if she needs to cough up a hairball. The love we share is anything but unconditional, which leaves me no choice but to fully commit to making it work—that, or I can always let her go.

Endnotes

1. Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto, p. 104

2. Morton, Timothy. “Subscendence” E-flux Journal, Issue #85. October 2017.

3. Margolies, Jane. “Could Oreo Cookies Solve New York’s Rat Problem?” NYTimes, Dec. 17 2021

4. Leland, John. “Your Dog Is Not Ready for You to Return to the Office” NYTimes May 19, 2022

5. Lamarre, Thomas. “Speciesism, Part III: Neoteny and the Politics of Life”, Mechademia Second Arc, January 2011, p. 117